Focus on Bilingualism: Korean: Language History, Culture and Comparison to English

by: Ellen Kester & Alejandro Brice

The Korean-American population has been growing steadily since the 1990 census and continues to increase. As such, the number of school children who speak Korean and English is increasing and it is important for speech therapists to understand the cultural and linguistic characteristics of the Korean population. Below is an excerpt from a more detailed article on Korean that will appear online in the Texas Speech-Language Hearing Association’s Communicologist. The article will include information about the history of the Korean Language, its written forms, cultural details, and Korean age of acquisition information.

Culture and Language

Koreans follow the Confucian tradition of communicating with others according to hierarchical relationships. The primary determinant of the hierarchical relationships is age. From a Korean cultural perspective, requesting information about age, marital status, job position, and wealth is acceptable and determines which language form one should use. Women use a softer tone than men and often introduce themselves as one’s wife or mother before providing their own name.

Phonology

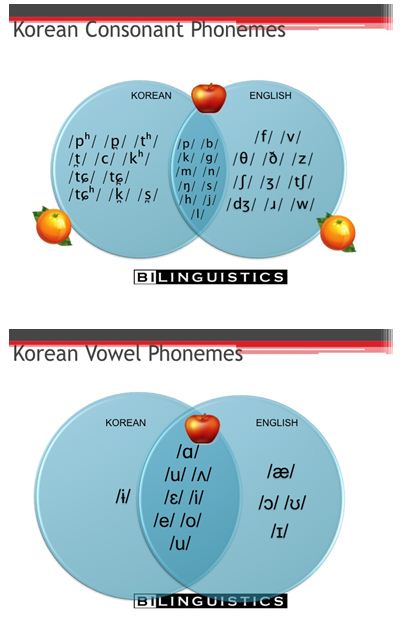

Korean phonology includes up to 21 consonants and 8-10 vowels, depending on dialect. Phonemes vary according to dialect. Consonants generally consist of plosives, nasals, fricatives, a glide and a liquid. Several consonant classes have up to three variations of place. For example, there are three bilabial stops /p, p̪, pʰ/, three alveolar stops /t, t̪, tʰ/, and three velar stops /k, k̪, kʰ/. The Korean consonant and vowel phonemes, contrasted with English, are included in the charts below. English and Korean share 13 consonant phonemes and there are 11 English phonemes that do not exist in Korean. Korean speakers learning English often interchange /ɹ/ and /l/, and may also nasalize final stops if they appear prior to a nasal sound (Cheng, 1991).

Phonotactics

In Korean, all consonants may occur in syllable-initial position, except for /ŋ/. Only seven consonants occur in syllable-final position: /p, t, k, m, n, ŋ, l/. Fricatives and affricates do not appear in word-final position. Thus, a word such as “bath” might be pronounced “bat.” Consonant clusters only occur in intersyllabic positions, and are not allowed in initial or final syllable positions.

Korean consists of about seven monophthongs, and ten diphthongs. Diphthongs are monophthongs combined with the semivowels /j/, /w/ and /ɰ/. Korean words often have stress on the first syllable; however stress is not used to differentiate word meaning. Therefore, Korean speakers learning English may use monotone stress.

Language Structure

The most common sentence structure in Korean is subject-object-verb. Word order is more flexible than in English but the verb is required to stay at the end of a sentence. Similar to English, modifiers typically precede the noun. Similar to German, Korean is an agglutinative language, indicating that morphemes are joined together. Due to this property, one word could represent a complete sentence. Articles and gender are not used in Korean.

While in English words are inverted to create a question, Korean utilizes stress to differentiate questions and statements. This is similar to Spanish, which uses a rising final intonation to denote a question, rather than changing word order.

Information provided in this article serves to assist in the differentiation of linguistic differences versus disordered behaviors to decrease the possibility of a misdiagnosis secondary to characteristics associated with cultural differences or second language learning behaviors.

References

Cheng, L. (1991). Assessing Asian language performance: Guidelines for evaluating limited-English proficient students (2nd ed.). Oceanside, CA: Academic Communication Associates.

Farver, J. M., Kim, Y. K., & Lee, Y. (1995). Cultural differences in Korean- and Anglo-American preschoolers’ social interaction and play behaviors. Child Development, 66, 1088- 1099.

Farver, J. M., & Shinn, Y. L. (1997). Social pretend play in Korean- and Anglo- American pre-schoolers. Child Development,68 (3), 544-556.

Kim, M. (2006). Phonological error patterns of preschool children for “Korean Test of Articulation and Phonology for Children” [In Korean]. Korean Journal of Communication Disorders, 11 (2), 17-31.

Kim, M. and Pae, S. (2005). The percentage of consonants correct and the ages of consonantal acquisition for “Korean Test of Articulation for Children” [in Korean]. Korean Journal of Speech Sciences, 12(2), 139-152.

Kim, Y. (1996). The percentage of consonants correct (PCC) using picture articulation test in preschool children. Korean Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 2, 29-52.

Kim, Nam-Kil (1987). Korean. The World’s Major Languages. Bernard Comrie (ed.). Rutledge. London: Croom Helm.

McLeod, Sharynne (2007). The International Guide to Speech Acquisition. Clifton Park: Thompson Delmar.

Oum, J. (1994). Speech sound development: Three, four, and five year-old children [in Korean]. In Korean Society of Communication Disorders (Ed.), The treatment of articulation disorders for children (pp. 54-66). Seoul: Kunja Inc.

Pae, S. (1995). The development of language in Korean children [in Korean]. In Korean Society of Communication Disorders (Ed.), Training of speech pathologists (pp. 18-35). Seoul: Hanhaksa.

Websites with cultural and linguistics information about Korean

Korea 4 Expats. http://www.korea4expats.com/article-people-culture.html.

The Korean Learner of English: English-Korean Cross-Linguistic Challenges

This Month’s Featured Authors:

Alejandro Brice, Ph.D., CCC-SLP University of South Florida St. Petersburg

Ellen Kester, Ph.D., CCC-SLP Bilinguistics, Inc.

Dr. Alejandro E. Brice is an Associate Professor at the University of South Florida St. Petersburg in Secondary/ESOL Education. His research has focused on issues of transference or interference between two languages in the areas of phonetics, phonology, semantics, and pragmatics related to speech-language pathology. In addition, his clinical expertise relates to the appropriate assessment and treatment of Spanish-English speaking students and clients. Please visit his website at http://scholar.google.com/citations?user=LkQG42oAAAAJ&hl=en or reach him by email at [email protected]

Dr. Ellen Kester is a Founder and President of Bilinquistics, Inc. http://www.bilinguistics.com. She earned her Ph.D. in Communication Sciences and Disorders from The University of Texas at Austin. She earned her Master’s degree in Speech-Language Pathology and her Bachelor’s degree in Spanish at The University of Texas at Austin. She has provided bilingual Spanish/English speech-language services in schools, hospitals, and early intervention settings. Her research focus is on the acquisition of semantic language skills in bilingual children, with emphasis on assessment practices for the bilingual population. She has performed workshops and training seminars, and has presented at conferences both nationally and internationally. Dr. Kester teaches courses in language development, assessment and intervention of language disorders, early childhood intervention, and measurement at The University of Texas at Austin. She can be reached at[email protected]

PediaStaff is Hiring!

All JobsPediaStaff hires pediatric and school-based professionals nationwide for contract assignments of 2 to 12 months. We also help clinics, hospitals, schools, and home health agencies to find and hire these professionals directly. We work with Speech-Language Pathologists, Occupational and Physical Therapists, School Psychologists, and others in pediatric therapy and education.