D.I.R. ® Model And Floortime™

By, Krystal Vermeire, OTR/L

D.I.R. ® Model: Refers to the theoretical model of childhood intervention. The ‘D’ correlates with development, ‘I’ with individual differences, and ‘R’ with relationships.

Floortime™: Refers to the intervention approach under the D.I.R. ® Model. It is the process of taking the information of the D.I.R. ® Model and applying it to practice. I have spent a great deal of hours completing tutoring, reading books, watching and attending lectures, and engaging in self-reflection to reach the comfort level I have with using the D.I.R. ® Model. For more information, including videos and archived podcasts, as well as links to informational resources and future conferences please see: www.icdl.com.

Let us first explore the “D” of the D.I.R. ® Model:

Developmental:

This aspect of the model refers to development in relation to discipline specific contexts: motor, speech, cognition, social, etc. This is where all the different disciplines come into play; developmental pediatricians, psychologists, social workers, occupational therapists, physical therapists, speech and language therapists, and the list goes on and on. Additionally, across disciplines, those familiar with the D.I.R. ® Model will assess and address the capacities of social-emotional development, also referred to as functional emotional capacities. It is important to keep in mind that in order to assess atypical development effectively, one must have a strong understanding of typical development.

There are many challenges in terms of development of a child. Many parents are not equipped with adequate knowledge of child development. School systems push for skills before they are typically expected in natural development. Doctors take on a “wait and see” approach when parents voice concerns. Another challenge area is traditionally there is limited and communication between disciplines. Each discipline traditionally keeps to a very narrow view of only their aspect of the child’s development. However, each aspect does not occur independently, rather the child is a dynamic being with development occurring across domains continuously over time. By staying so narrow, professionals are missing out on the ‘big picture’ of the whole child.

In order to move forward in the future and maximize service delivery and development, it is important for communication across professional disciplines and service settings. I always encourage parents to please share information between therapists, doctors, schools, and specialists. I encourage parents to know what their priorities are for treatment and make them clear to the therapists and professionals working with their child. I want to empower parents to feel confident in being their child’s best advocate.

As professionals, we must keep in mind that progress in all areas of development is interrelated. It is important to observe and assess the integration of motor skills, language skills, cognition, and social-emotional skills, etc. rather than unnaturally separating them out from one another. This is why a team approach works best, but also this is why it is important for each discipline to have a very basic understanding of the other disciplines. We need to know when to refer out when someone is not quite right. Language and cognition, as well as emotional and social skills, are learned through relationships that involve emotionally meaningful exchanges. Children and adults vary in their underlying motor and sensory processing capacities. It is the whole child that we must keep in mind as we are assessing and treating these children.

Under the D.I.R.®/Floortime™ Model, there are functional emotional capacities, also referred to as social-emotional developmental levels. Essentially, there are three stages of these levels. The first is the six core capacities that take place between birth and four years of age in typical development. These core capacities lead to complex thinking, which includes the next stage of developmental levels. This next stage, which essentially builds on the child’s development of complex thinking and reasoning skills, typically takes place roughly between ages five and eleven. Again, this is in typical development. The final stage includes the levels of adolescence and adulthood, which lead to greater self-awareness and reflection. These levels may not be fully mastered for the average person, but are outlined as possibilities for mastery across the lifespan.

The first stage includes the six core capacities (typically achieved birth to 4 years):

1: regulation and shared attention

2: engagement/relationship

3: reciprocity

4: problem solving, increased circles of communication

5: symbolic play and thinking

6: logical sequencing, critical thinking

Regulation and Shared Attention:

Regulation means more than appearing calm. Many children can appear calm and not be regulated. Co-regulation occurs when two people are connected and one helps to regulate another. Regulation is similar to the idea of sensory modulation. It is the ability to achieve and sustain homeostasis from within the body. Shared attention involves sharing an experience in an interaction (dyad). A dyad occurs between two people or between one person and an object. When shared attention is weak, it makes it hard to move ahead. Shared attention includes social referencing, shared gaze, and beginnings of communication. For many children, this can be the most challenging level. They might have progressed on to higher levels of development, but they still struggle with sharing gaze, visual referencing across space, and sharing interactions and experiences with others.

Engagement:

Dr. Greenspan described this as “falling in love”. It is the building of relationships. In typical development, this occurs very young as the mother and baby share many close and intimate moments during feedings, diaper changes, etc. Joint attention occurs at this stage. Joint attention is when the baby can share attention in a triad context. A triad is the interaction between three people or two people and an object.

Attachment is a separate topic, but one of significant importance. I could do a whole lecture on attachment. Attachment occurs very young and has lasting impacts on development throughout life, as well as parent-child interaction patterns and patterns of interaction between the child and others. Attachment is a challenging thing to secure if level 1 & 2 capacities are compromised.

All too often, children are progressing up the developmental ladder and working on complex problem solving, critical thinking skills, and reflective thinking; however they have a weak foundational bases in regulation, shared attention, and engagement. This leads to “meltdowns” and other such behaviors, because the demands placed on the child are too overwhelming for their regulatory and emotional capacities. In the future, I urge you to take a step back and really look at how the child is functioning. Are they regulated? Can they share attention with you around a play interaction, a.k.a. shared experience? Can they engage with you where you feel like you are connected and together in the moment? If there is any doubt what-so-ever, then your child can benefit from starting with the basics. It is like building a house, you would not start with the roof and work your way down to the foundation, right? Then why is this the way we approach child development and learning. Traditionally and in behavior based approaches, there is little emphasis on supporting them and too much emphasis on directing them.

Reciprocity:

This is where we begin to see “circles of communication,” or back and forth interactions between the child and another person. Relationships are powerful in motivating a child’s development forward: by developing the early back and forth interactions the child is able to expand to more complex thoughts and conversations. Reciprocity means more than talking…while having a verbal exchange is a reciprocal task, so is playing catch, rolling a car, playing chase games, and communicating via gaze and body language.

Language progresses along a continuum. Being that I am an occupational therapist, I cannot give specifics, as I am not fully trained in language acquisition. I can support the importance of having a basic idea of this progressive continuum. Language is everything, or at least a lot…I know as a parent, you want your child to talk. That is often an initial reason for seeking out services. An introductory understanding of language acquisition is helpful to all those working and interacting with children. Language has an influence and impact on all other aspects of intervention. Language is how we interact with one another and yet it is not widely understood.

Problem Solving, Increased Circles of Communication:

As a child increases their reciprocity, the length and quality of communication expands. We can look at two aspects of problem solving: shared social problem solving and independent problem solving. Shared-social problem solving: with good earlier capacities, children and their caregivers can work together to find appropriate resolution to challenges. This is a shared experience; focus is on the process of problem solving, rather than the end result. Independent problem solving: when the child can problem solve without the support and assistance of another. Many children will try to figure things out by themselves, but cannot remain regulated while doing so and therefore need more shared-social problem solving.

Symbolic Ideas:

This is when children begin to explore their environments and develop symbolic representations and ways of communicating. They are using words and gestures to communicate. They are playing with toys and engaging in more pretend play. Initially pretend play is more concrete, and then it expands to more complex and abstract. The best way to promote this capacity is by joining your child in shared experiences.

Logical Sequences and Emerging Critical Thinking:

Children at this stage are starting to string together thoughts in more logical ways, building bridges between ideas. Play is starting to make more sense. Interactions are beginning to be more complex. Play is a natural vehicle for learning. “Play for children is not just a recreation activity,… It is not leisure-time activity nor escape activity… Play is thinking time for young children. It is language time. Problem solving time. It is memory time, planning time, investigation time. It is organization-of-ideas time, when the young child uses his mind and body and his social skills and all his powers in response to the stimuli he has encountered (Hymes, 1968).”

I think it is important to take another look at how we think about play. The child’s play is a reflection of their cognitive, social, affective, and language development. Early language acquisition and symbolic play development are linked as manifestations of representational capacity. The child’s language and conversational development as well as their cognitive, social, and affective development can best be facilitated in the context of play interactions. Changes in play can lead to changes in language and development. “Play permits the child to resolve in symbolic form unsolved problems of the past and to cope directly or symbolically with present concerns. It is also the child’s most significant tool for preparing himself for the future and its tasks (Bettleheim, 1987).”

Things to keep in mind during play…

- Intrinsic motivation: Children play because they want to.

- Process over product: When playing with children, the adult should be more invested in the ongoing activity and interaction than on a specific goal.

- Child structured: Let the child direct the play, it builds self-esteem, promotes problem solving, and drives development.

- Active engagement: There should be direct participation of all involved. You should be sharing in the experience together.

- Free choice: Young children may not be interested in the choices for play that adults tend to bring to offer.

- Positive affect: Play should be fun and happy, let that reflect in your facial expressions, words, and body language. Enjoy your children!

- Intrinsic rules: Keep rules and structure simple. The more you pile on, the less room there is for fun.

- Non-literal activity: Play is play; it does not have to make sense.

I think it is important above all, to consider the child’s interests when setting up the environment for play. It is our role as therapists to set the stage and be a play partner. “It may look as though the child at play is not learning anything, but actually he is…learning how to learn (Ayres, 2005).”

Higher Level Capacities of Complex Thinking:

- 7: Multi-Cause and Triangular Thinking

- 8: Gray-Area, Emotionally Differentiated Thinking

- 9: A Growing Sense of Self and an Internal Standard

Stages of Adolescence and Adulthood:

- 10: An Expanded Sense of Self

- 11: Reflecting on a Personal Future

- 12: Stabilizing a Separate Sense of the Self

- 13: Intimacy and Commitment

- 14: Creating a Family

- 15: Changing Perspectives on Time, Space, the Cycle of Life, and the Larger World: The Challenges of Middle Age

- 16: Wisdom of the Ages

Now let’s take a look at the “I” of the D.I.R. ® Model:

Individual Differences:

We are all unique; no two people are exactly the same. The profiles of the child and each of their family members needs to be factored together for an accurate picture of the child that includes sensory processing and modulation, readiness for change and learning, and patterns of attachment. This must all be taken into account when working with children and their families.

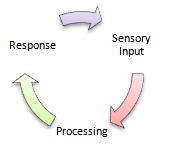

Sensory integration is the process of taking in sensory information and generating a response to the input received. We receive sensory information from all our senses to generate responses and interactions with others and the environment. Sensory integration occurs in the process of a feedback loop, as seen in this illustration:

There are many opportunities for things to go wrong in the processing of sensory input. Children may have difficulty sensing information coming in, filtering information for appropriate use, or in the motor aspect of using sensory information for output, behavior and motor actions. The process of regulating and filtering sensory information for appropriate arousal and behavioral responses to sensory inputs is known as sensory modulation. Sensory modulation occurs along a continuum: Failure to Orient Optimal Arousal – Over Orientation.

When children are not able to achieve and sustain optimal arousal, they are said to be over-responsive or under-responsive to sensory input. It is entirely possible for a child to be over-responsive to one sensory input, such as tactile, but under-responsive to another sensory input, such as visual. Additionally, it is not altogether uncommon for a chid’s responsivity to change from day to day or even moment to moment. Children are unique and unpredictable at times and our job is to just do our best to help them in whatever arousal state they are in to achieve and sustain optimal arousal.

Last we will explore the “R” of the D.I.R. ® Model:

Relationships:

Eliciting true and lasting change cannot happen by treating the child alone. It cannot be achieved in weekly therapy sessions, even if we saw the children 5-7 days a week. Families need to be a part of the treatment process. Traditional medical models of intervention focus on professional directed intervention without regard to the child’s interests or parent involvement. This needs to change. Some focus of treatment needs to be placed on the relationship between the child and their parents, siblings, and caregivers. Without these relationships treatment has limitations to effectiveness.

We must remember to work from the bottom up, rather than top down. This is achieved by focusing on where the child is developmentally, keeping in mind their unique and individual profile, and treating in the context of a relationship or shared experiences. There will come a time when top down approaches are appropriate, but always be mindful of the support that is needed on the bottom level for this to occur effectively. All the skills in the world are only relatively useful if not in the context of a relationship. We should meet the child where they are at and pay attention to what they are bringing to the table.

Another important aspect to consider is us and our unique profiles. We need to carefully consider our individual differences and be able to manage them in order to best support the child. This is easier said than done, especially in stressful moments. It is important for therapists to engage in reflective practice. This is also important for parents. It means that time is spent reflecting on situations or interactions that might not have gone as planned and thinking out possible alternative solutions for the next time they occur. Developing mindfulness: being aware of what you are bringing to the table so that it can minimally conflict with promoting development of the child you are working with.

It is important to have a support network for both therapists and parents. For therapists, it is important to work with team members and get necessary support for better outcomes. For parents, it is important to have a supportive network of professionals and friends to lean on when things are particularly hard. It is our job as professionals to encourage parents to look for resources in the community, meet up with other parents, and give themselves a safety net of support.

Lastly we must examine the role of a parent on their child’s treatment team. The idea that parents should be a member of their child’s treatment team is a variable subject. It is my firm belief that the efforts the parents put forth in mobilizing their child’s development is what creates lasting change. Therapists can only do so much in the short time they are with a child. In the end, the bulk of the work falls on the parent’s, shoulders. Therapists can provide parents with the tools, knowledge, and comfort to get the job done.

References:

Ayres, A.J. (2005) Sensory Integration and the Child: Understanding Hidden Sensory Challenges. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services.

Bettleheim, B. (1987). A Good Enough Parent: A Book on Child Rearing. New York, NY: Random House.

Hymes, Jr., J. (1968). Teaching the Child Under Six. Columbus, OH: C.E. Merrill Publishing Company.

Resources I have read in the past that contributed to the knowledge presented in this article.

Greenspan, S.I. & Wieder, S. (2006) Engaging Autism: Using the Floortime Approach to Help Children Relate, Communicate, and Think. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press.

Greenspan, S.I. & Shanker, S.G. (2004) The First Idea: How Symbols, Language, and Intelligence Evolved from Our Primate Ancestors to Modern Humans. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press.

ICDL Graduate School Faculty-personal communications

Siegel, D. & Hartzell, M. (2004). Parenting From the Inside Out. New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher/Putnam.

www.icdl.com

www.zerotothree.org

Featured Contributor: Krystal Vermeire, OTR/L

Krystal Vermeire, OTR/L has been practicing pediatric occupational therapy since 2007 in private clinical settings. She is Sensory Integration certified, allowing her to administer and interpret the Sensory Integration and Praxis Tests. Krystal enjoys working with children of all abilities. In her spare time, she leads her daughter’s Girl Scout troop and is working towards her Ph.D. in Infant and Early Childhood Mental Health and Developmental Disorders through ICDL Graduate School. Krystal has taken many continuing education courses, including DIR/Floortime, Beckman Oral Motor Protocol, Interactive Metronome, Myofascial Release, Kinesio Taping techniques, Yoga for Kids, Therapeutic Listening, Sensory Integration and Praxis, and Hippotherapy. Currently, Krystal is employed as the Supervisor of Occupational Therapy Services at All For Kids Pediatric Clinic in Anchorage, AK where she provides clinic, home-based, aquatic, and hippotherapy services in addition to supervising and mentoring staff.

PediaStaff is Hiring!

All JobsPediaStaff hires pediatric and school-based professionals nationwide for contract assignments of 2 to 12 months. We also help clinics, hospitals, schools, and home health agencies to find and hire these professionals directly. We work with Speech-Language Pathologists, Occupational and Physical Therapists, School Psychologists, and others in pediatric therapy and education.